![]()

Three Faiths under

One Roof

by Fr. Dave Denny

Ever since moving into my new home, which

is called al Hadiyah (Arabic for

“the gift”), I have greeted

visitors with my favorite Arabic greeting:

Ahlan wa sahlan, which means,

roughly translated, “These are your

people and may this be your welcoming land.”

Although it may not be the first thing

you notice, you step into the entry gallery

and onto a red and black carpet given to

me in 1970 in Afghanistan. I was an exchange

student there, and despite having learned

in my orientation not to compliment Afghans

on their belongings, I blurted out one

day in my family’s home in Herat,

“What a beautiful rug!” The

next thing I knew, it was mine. That’s

part of the Afghan code of hospitality:

if a guest admires a host’s possession,

he or she gives it away, even if it costs

the owner dearly. Although I felt some

sheepishness in accepting the gift, I am

grateful. I could not have known at age

seventeen how profoundly my life would

be shaped by those months in a Muslim household

halfway around the world.

Ever since moving into my new home, which

is called al Hadiyah (Arabic for

“the gift”), I have greeted

visitors with my favorite Arabic greeting:

Ahlan wa sahlan, which means,

roughly translated, “These are your

people and may this be your welcoming land.”

Although it may not be the first thing

you notice, you step into the entry gallery

and onto a red and black carpet given to

me in 1970 in Afghanistan. I was an exchange

student there, and despite having learned

in my orientation not to compliment Afghans

on their belongings, I blurted out one

day in my family’s home in Herat,

“What a beautiful rug!” The

next thing I knew, it was mine. That’s

part of the Afghan code of hospitality:

if a guest admires a host’s possession,

he or she gives it away, even if it costs

the owner dearly. Although I felt some

sheepishness in accepting the gift, I am

grateful. I could not have known at age

seventeen how profoundly my life would

be shaped by those months in a Muslim household

halfway around the world.

Contemplative Christianity

As

I went on to college and university, I

felt drawn to contemplative Christianity,

a tradition that was willing to listen

to and learn from other cultures and religions.

I discovered Thomas Merton and Bede Griffiths.

I hungered for a Christianity that reflected

the wide-open arms of the Jewish rabbi

whom I believe is the embodiment of God.

I could find no condemnation of the “other”

in the Gospel. On the contrary, Jesus shocked

friend and foe by his openness to the “other,”

the alien, the “un-chosen,”

and communicated a sense of truth through

communion and compassion, not through the

unilateral imposition of an ideology. Having

studied Arabic and Islam in college, I

put my interest in the other Abrahamic

traditions aside for decades as I deepened

my immersion in the Carmelite tradition

and the Christian mystics. But after 9/11

and a seismic and shift in my own vocation,

I longed to return to the teachings and

history of the other Abrahamic traditions.

When Tessa Bielecki and I created the Desert

Foundation and I found myself in a new

house that was a blank canvas, I began

to dream about what kind of art might surround

me in this new life.

As

I went on to college and university, I

felt drawn to contemplative Christianity,

a tradition that was willing to listen

to and learn from other cultures and religions.

I discovered Thomas Merton and Bede Griffiths.

I hungered for a Christianity that reflected

the wide-open arms of the Jewish rabbi

whom I believe is the embodiment of God.

I could find no condemnation of the “other”

in the Gospel. On the contrary, Jesus shocked

friend and foe by his openness to the “other,”

the alien, the “un-chosen,”

and communicated a sense of truth through

communion and compassion, not through the

unilateral imposition of an ideology. Having

studied Arabic and Islam in college, I

put my interest in the other Abrahamic

traditions aside for decades as I deepened

my immersion in the Carmelite tradition

and the Christian mystics. But after 9/11

and a seismic and shift in my own vocation,

I longed to return to the teachings and

history of the other Abrahamic traditions.

When Tessa Bielecki and I created the Desert

Foundation and I found myself in a new

house that was a blank canvas, I began

to dream about what kind of art might surround

me in this new life.

Some may imagine that spirituality is not about matter. But Jesus loved lilies, good food and friendship, wine and walking under the sun and stars. In fact, according to John the Evangelist, Jesus incarnated the Word and the Word loved these worldly wonders into being. I recall a poem, “Things,” by Spanish poet Gloria Fuertes: “These things, our things, / how they want to be wanted! / … the door asks to be opened and closed, / the wine to be purchased and drunk, …” I wanted my door to open to a world, not just a house, to things that mean beauty to me, images that want to be wanted, that want to tell stories. I wanted to bring together manifestations of beauty from peoples separated by conflict: the sons and daughters of Abraham, our father in faith. Even if for now we cannot or will not live together in peace and justice, I wanted our handiwork to share a common ground, to suggest a premonition of reconciliation.

Solitude and Hospitality

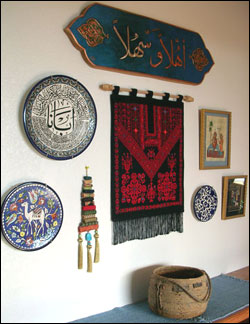

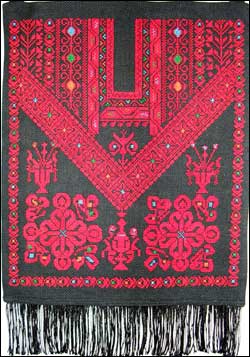

The

first thing you may see when crossing the

threshold of al Hadiyah is an

embroidered cloth hanging with shimmering

red geometrical patterns on a black background.

It was woven by women of Beit Jala, a village

near Bethlehem. Its dominant colors are

the same as the Afghan rug, and although

Afghanistan is far from Palestine, and

its culture is not Semitic, the patterns

of their textiles share similarities. Many

Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza

Strip cannot enter Jerusalem, so a nonprofit

called Sunbula gathers Palestinian crafts

for sale at a shop sponsored by St. Andrew’s

Church in Jerusalem. That’s where

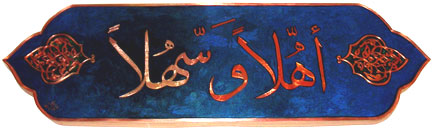

I found this hanging. Above it hangs an

ornate sign proclaiming “ahlan wa

sahlan” in Arabic calligraphy and

crafted by a Jewish friend, Shahna Lax,

here in Crestone. The greeting may be Arabic,

but it belongs to no single religion or

scripture. It is a simple offering of the

hospitality that reigns throughout the

Middle East and has roots in desert Bedouin

traditions. I want to offer that kind of

hospitality in my home, even though I live

as a solitary.

The

first thing you may see when crossing the

threshold of al Hadiyah is an

embroidered cloth hanging with shimmering

red geometrical patterns on a black background.

It was woven by women of Beit Jala, a village

near Bethlehem. Its dominant colors are

the same as the Afghan rug, and although

Afghanistan is far from Palestine, and

its culture is not Semitic, the patterns

of their textiles share similarities. Many

Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza

Strip cannot enter Jerusalem, so a nonprofit

called Sunbula gathers Palestinian crafts

for sale at a shop sponsored by St. Andrew’s

Church in Jerusalem. That’s where

I found this hanging. Above it hangs an

ornate sign proclaiming “ahlan wa

sahlan” in Arabic calligraphy and

crafted by a Jewish friend, Shahna Lax,

here in Crestone. The greeting may be Arabic,

but it belongs to no single religion or

scripture. It is a simple offering of the

hospitality that reigns throughout the

Middle East and has roots in desert Bedouin

traditions. I want to offer that kind of

hospitality in my home, even though I live

as a solitary.

This copper and blue-green

enamel sign mounted on cedar, created by

Shahna Lax, displays the Arabic greeting

“Ahlan wa Sahlan.” These fluid

copper letters tumble across the enamel

like sunlight on blue water to greet visitors

to my hermitage.

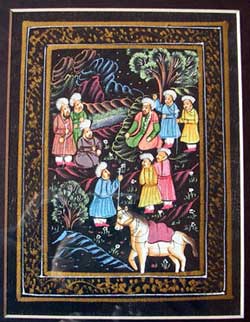

The

wall includes a small Persian miniature

of nine men meeting on a verdant hillside.

A white pony stands in the foreground beside

a stream. Like my rug, it reminds me of

Afghanistan. I remember standing with my

Afghan “brother,” Syed Ahmad,

one evening thirty-seven years ago at a

place called Bagha Bala (High Garden) outside

Kabul. The heat of the day waned; a breeze

blew through the fruit trees; the lights

of kerosene lamps began to appear from

within the flat-roofed adobe homes below

us. The full moon rose, and I felt I was

inside a Persian miniature, a landscape

and atmosphere that, until that moment,

would have seemed purely fictional to me,

a son of the green flat farmlands of northern

Indiana.

The

wall includes a small Persian miniature

of nine men meeting on a verdant hillside.

A white pony stands in the foreground beside

a stream. Like my rug, it reminds me of

Afghanistan. I remember standing with my

Afghan “brother,” Syed Ahmad,

one evening thirty-seven years ago at a

place called Bagha Bala (High Garden) outside

Kabul. The heat of the day waned; a breeze

blew through the fruit trees; the lights

of kerosene lamps began to appear from

within the flat-roofed adobe homes below

us. The full moon rose, and I felt I was

inside a Persian miniature, a landscape

and atmosphere that, until that moment,

would have seemed purely fictional to me,

a son of the green flat farmlands of northern

Indiana.

Pottery

and Paradise

Pottery

and Paradise

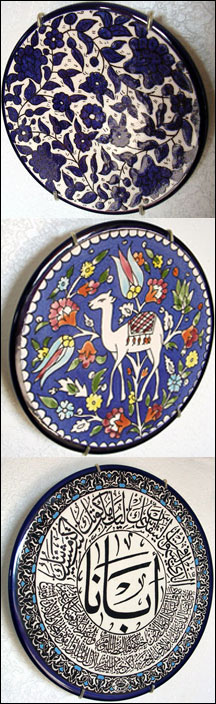

Three ceramic plates hang on the wall.

Made by Christian potters in Bethlehem,

one is glazed with the Our Father in Arabic.

I have memorized the first Sura of the

Qur’an; it’s time I memorized

the Our Father in Arabic. A simple blue

and black floral pattern covers a smaller

dish, testifying to desert dwellers’

fascination with flowers and gardens: a

reminder that our word “paradise”

comes from the Persian word for garden.

A stately white camel stands in silhouette

against a floral background on the third.

This appeals to me for two reasons. Most

immediately, it reminds me of March 2000,

when I rode a camel for two days in the

desert of Wadi Rum, near Aqaba, Jordan.

Seated high on the camel’s back I

wandered through a maze of sun-drenched

and shadowed red cliffs on sands that shifted

from beige to ochre to rust. Spring rains

allowed tiny wildflowers to spring up in

impossible crannies of sand and stone.

Before and after my little expedition,

my teen-aged camel driver’s mother

sat me down next to her charcoal fire in

her enclosed patio to drink sweet hot tea

spiced with sage.

But the camel also reminds me of the Jewish

tradition, of their sojourn in Sinai, and

Isaiah’s vision of the day when all

nations will come to Jerusalem, drawn by

the truth and light it radiates:

Then you will see and be radiant,

And your heart will thrill and rejoice;

Because the abundance of the sea will be

turned to you,

The wealth of the nations will come to

you.

A multitude of camels will cover you,

The young camels of Midian and Ephah;

All those from Sheba will come;

They will bring gold and frankincense,

And will bear good news of the praises

of the Lord.

(Isaiah 60: 5-6)

Sanctuary, Not Separation

On

the center of the bookshelf as you enter

lies a worn and empty basket. It

comes from the Egyptian oasis of Siwa,

an ancient settlement visited by

Alexander the Great before there was such

a thing as a Christian or a

Muslim. It is tattered but tightly woven.

I like to think it holds nothing

but Promise.

On

the center of the bookshelf as you enter

lies a worn and empty basket. It

comes from the Egyptian oasis of Siwa,

an ancient settlement visited by

Alexander the Great before there was such

a thing as a Christian or a

Muslim. It is tattered but tightly woven.

I like to think it holds nothing

but Promise.

A wall can be a terrible thing. I want the wall that people see when entering my home to be a sign not of separation, but of sanctuary, protection, hospitality. I want it to show that beauty is not monopolized by one tradition, but shared by all. I want it to show you what Paradise might look like through the prism of my desert sojourns with Jews, Muslims, and Christians in our troubled Abrahamic family.