![]()

Death and Life Go On

by David M. Denny

Driving to Aspen from my home in Crestone, Colorado took me north past Twin Lakes, uphill through aspen groves, along frothy white cataracts, around hairpin curves to Independence Pass, where, between slushy patches of snow, tiny alpine wildflowers blossomed. As I descended westward from tundra to timberline toward Aspen's luxury, I thought about how I am still stunned by American affluence, more than forty years after visiting Afghanistan in 1970. I have visited countries with one or two cosmopolitan cities where wealth blossoms like alpine flowers. But in America, in every state, palaces sprout like weeds. We call them houses.

It struck me particularly this time because the man I went to see in Aspen was born in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1965. When he was five years old, I was seventeen and arrived in Kabul as an exchange student with the American Field Service. I wondered what it was like for him to have spent his first eleven years in Kabul, then move to Paris, and on to California in 1980 after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. These are very different worlds. I recall how frustrating it was when young Afghans asked me about America. All they had experienced were Elvis Presley movies and hearsay about Disneyland. That was not the America I knew. As I descended into Aspen, it occurred to me that maybe those fantasies sprouted from a grain of truth. But as years went by, war became a way of life in Afghanistan, Americans arrived to drive out the Taliban, and the image of America surely shifted. Celluloid Elvis became a living soldier armed with sophisticated weapons patrolling a Kandahar street; Disneyland gave way to fighter jets and drones raining down hellfire. Meanwhile young Khaled Hosseini learned English in California.

It struck me particularly this time because the man I went to see in Aspen was born in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1965. When he was five years old, I was seventeen and arrived in Kabul as an exchange student with the American Field Service. I wondered what it was like for him to have spent his first eleven years in Kabul, then move to Paris, and on to California in 1980 after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. These are very different worlds. I recall how frustrating it was when young Afghans asked me about America. All they had experienced were Elvis Presley movies and hearsay about Disneyland. That was not the America I knew. As I descended into Aspen, it occurred to me that maybe those fantasies sprouted from a grain of truth. But as years went by, war became a way of life in Afghanistan, Americans arrived to drive out the Taliban, and the image of America surely shifted. Celluloid Elvis became a living soldier armed with sophisticated weapons patrolling a Kandahar street; Disneyland gave way to fighter jets and drones raining down hellfire. Meanwhile young Khaled Hosseini learned English in California.

After wandering in bewilderment through Aspen Institute's vast campus I found Hosseini onstage at the Doerr-Hosier Center. In 2003 his novel, The Kite Runner, took the world by storm. As I entered the auditorium, Iranian American writer Firoozeh Dumas was asking Hosseini if he always thought of himself as a writer. Although from childhood he loved stories, he never considered writing as a possible career. In fact, he said, even after the success of The Kite Runner, he didn't think of himself as a writer until he was watching Jeopardy on TV one day and his name came up as an answer. Then he decided to stop practicing medicine at Cedars-Sinai hospital in Los Angeles.

When I read The Kite Runner, I loved Hosseini's descriptions of Kabul in the 1970s. They reminded me of the neighborhood called Jamal Menna, where I lived with the Azad family. Hosseini said that he grew up in circumstances similar to Amir's, the young son of a prominent Afghan family. Hosseini's father was a diplomat, and his mother taught at a girls' high school. He also said that the descriptions of life in California - driving around in a big van to weekend flea markets where a tight-knit Afghan community met - is also an accurate description of his own life in California.

Dumas asked Hosseini what it was like to return to Afghanistan in 2003, after twenty-seven years away. He was stunned by the devastation. He reminded us that in the seventies, Kabul was a rather "cool" place. He didn't mention the drug scene that attracted some young westerners, but he did mention the cinemas, restaurants, and women's freedom to wear the veil or not in Kabul. Since the Taliban takeover, some westerners may have the impression that Afghans tend toward religious fanaticism, but Hosseini confirms that by nature Afghans are fairly liberal. The Taliban are not home-grown. They arose from refugee camps in Pakistan.

So Hosseini was overwhelmed by the number of widows, amputees, orphans, and old friends who were now homeless. Dumas asked if he felt a need to get involved in foreign policy that could help improve the situation. He said he is a writer, not a politician, but he hopes his stories will influence politicians' decisions.

As for positive changes, Hosseini said that seven million children are in school now, and thirty-five percent of the students are girls. Only eight percent of the population had access to health care under the Taliban; that number is now eighty percent. Twenty-five percent of the members of parliament are women. Nevertheless, the Afghanistan of 2003 broke his heart. He became a spokesman for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Thanks to his success as a writer, he launched the Khaled Hosseini Foundation and decided to focus on aid and development for the most vulnerable Afghans: returning refugees, women and children.

He described how difficult it is for refugees to reintegrate. Since 2002, up to eight million have returned, preferring their native land to Pakistani refugee camps. But homecoming sometimes meant two dozen people living in little more than a hole in the ground. Many children do not survive the winters. In partnership with UNHCR, Hosseini's foundation helped build 102 homes for more than six hundred Afghans in 2009.

Dumas asked Hosseini what he wants Americans to know about the Afghan people. He mentioned three myths he wants to dispel. First, the Afghans are not "stuck in the thirteenth century" or even the "stone age," as some westerners sometimes assume. He described meeting an elderly mullah in a remote mountaintop Hazara village where locals grow pistachios. The mullah handed Hosseini a note and told him to deliver it to President Karzai. It was a request for computers for the local school. He and many others in Afghanistan are eager for learning and economic development.

Second, as for Afghanistan as a warrior culture incapable of embracing peace, Hosseini insists that although tribes are proud, they share a common Afghan identity. He was particularly vehement as he noted that in the first half of the twentieth century, while the West engaged in two world wars that left millions dead, Afghanistan lived in peace. He also noted that very few international terrorists are Afghans. He could think of two.

Third, are Afghans ungrateful beggars? No. They long for independence from foreign support. But they are pragmatic, and in December 2009 seventy percent wanted foreign troops to remain in the country because they understand that in spite of the progress made since the expulsion of the Taliban, the situation is dire. Afghans fear the anarchy of civil war more than the Taliban. During the mayhem of the nineties, fifty to seventy thousand Afghans died in Kabul alone. Eight million refugees struggle to survive. One in five children still dies before age five. Seventy percent of the population is still illiterate. Reconstruction, Hosseini insists, is not a dash; it's a marathon.

Hosseini summed up by saying that mass media sometimes bolster these fallacies because some outlets have only one story. The tale of a medieval warrior culture that resents us makes news. A beautiful land once full of orchards and gardens that is struggling but able, with help, to grow and recover from decades of war, may not be such compelling reading. It is a complex story.

When asked about his writing method, Hosseini said he had no outline for The Kite Runner. He only knew it was a story about two boys from different backgrounds that made for a power differential between them, and that one boy would depart Afghanistan and return. He did not know in the beginning that the boys were brothers. The revelation came one day while he was shaving. He ran to his wife, razor in hand, face half covered in shaving cream, to announce this shocking discovery. In preparing to write A Thousand Splendid Suns, Hosseini took advantage of a lull in fighting to visit Afghanistan and interview Afghans from all walks of life. Women had suffered a double oppression: ideological misogyny and sexual violence. He wanted to explore unique lives of real women and dispel the abstraction of a "typical" Afghan woman hidden beneath a full-length veil.

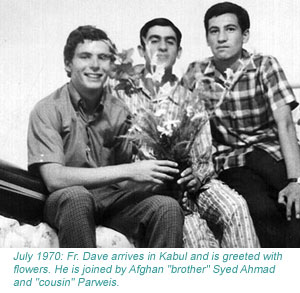

On my way home I thought about a memory I have recalled and recounted repeatedly in the past forty years. One spring day in 1970 my mother left a message at my high school to call her. She had never done that before. I called during lunch break and she said, "Dave, I found out where you're going this summer." I had dreamed for years of going abroad and had applied to be an American Field Service summer exchange student. I was studying French and probably harbored romantic hopes of meeting beautiful jeunes filles. My heart raced as I asked, "Where?!" She said, "Afghanistan." After a pause, I gasped, "Where is it?" She told me to find a map and look between Pakistan and Iran. It is difficult now to imagine a time when I did not know where Afghanistan is. Those few weeks there still mark my life, forty years later.

After his talk, Hosseini's young daughter ran up and threw her arms around him as he made his way to the auditorium's entry hall, where he would sign books. She is older now than he was when I walked the streets of Kabul. Life is short and long. War came to Afghanistan in 1979 and has not ceased. Death goes on. Seeing Hosseini and his daughter embrace in a land of plenty and domestic peace confirms the Afghan adage, repeated a few times in The Kite Runner: zendagi migzara, life goes on. For members of the Azad family who hosted me, life went on, too—in India, Germany, Canada and the United States. It is good to know that through his foundation, Hosseini helps life go on in his native land by providing shelter for refugee families and economic and education opportunities and healthcare for women and children. You may find out more about his work here.